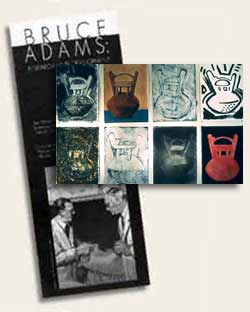

Bruce Adams: Research and Development

Bruce Adam's work has long been a vehicle of paradox. Serious allegiance to traditional figurative and narrative technique coexists with sly digs at art historical conventions and stylistic clichés. An obvious fascination with the nude female form is complemented by an equally conspicuous political awareness of sexism in both art and life. Humor abounds in the work, yet painstakingly earnest layers of ideological exegesis lie concealed beneath the humorous veneers. Adams has a huge subject--not just art history, but how that discipline can be understood or misunderstood through other scholarly methodologies, such as anthropology and archeology. He's able to pull it off, partially through his skeptical--thus paradoxical--reverence for the modernist master narrative. In lush, evocative testimony to the vigor of Adams' entire oeuvre, past and current, this exhibition allows the viewer to enjoy an amiable jostling match between visual pleasure and conceptual challenge.

The most recent paintings are the culmination of Adams' long-standing interest in "scientific" analysis of past and present culture. In earlier treatments, Adams presents deliberately ironic tableaus: Restoration (1988/1995), for example, shows two "scientists"--or at least two guys in white coats--arguing in the foreground while a languorous Titan nude (The Venus of Urbino) is glimpsed reposing behind them. In a recently-glimpsed "authority bite" from a standard art history text, David Piper stuffily asserts that the Titian is "of course, far more than a pin-up." Surprising that an art historian would go out of his way to deny a painting's potential for salacious voyeurism--protesting too much, surely, about an issue which is rarely brought up in a scholarly contest. In the 1988 version of the painting, Adams had an actual 1950s-style pin-up hanging behind the scientists' heads; in 1995 he changed it to a sculpted female figure. Adams isn't just capriciously appropriating. All three incarnations of the female form seem simultaneously debased and celebrated. It has to do with the dispassionate analysis of culture and civilization. Are paintings decoration, aphrodisiacs, moral parables, or historical "truth?" An important question, but one unlikely to be satisfied by scientific analysis.

In his recurrent use of three cultural artifacts--the classical sculpture, the vase, and the geometric form--Adams has invested his dichotomous exploration of science and art with an on-going narrative, a type of soap opera. Which character will turn up next, and what role will each play? The sculpture is the long-suffering heroine: will she ever get that arrow out of her back? The vase is dependable and versatile, a stylistic character actor and universal favorite, while geometric form is the surprise guest from the past, presumed dead but merely amnesiac. So the paintings work together: each context suggests different symbolic interplays. In Curator Irene Kühnel Inspects the Painted Canvas (1995), Adams' usual team of pale drab researchers (he finds the source images in 1940s-50s-era issues of National Geographic) grimly go about their task of assessing the physical dimensions of the geometric form. This is a painting, but it also retains the qualities of the "primitive object," while the sculpted figure hangs in the background as a pin-up, an icon of the figurative norm. Adams has invested this ridiculous tableau with a host of thematic undertones. Just one: An African-American attendant passively holds the painting, taking no part in the "research," reinforcing the "kept at arm's length" attitude towards alien cultures that runs through the whole series. It's also significant that Adams never really integrates his appropriated research team into the scene. They retain their lifted-from-the-pages-of-history quality. Do we really believe they¹re even looking at the painting?

Tableaus such as Restoration and Kühnel--coherent statements of Adams' conceptual intent--serve as introductions to a series of works on paper which explore variations of the basic themes. The series, "Research and Development" and "Men at Work," say as much about Adams' love of painting and pop culture as they do about definitions of culture. The "Men at Work" are briskly, expressively painted, in marked contrast to the careful realism of Adams' earlier works on canvas. The "Research and Development" vases are equally expressive, even playful in their exploration of various painting styles. These works are really the breakthrough works of Adams' recent career; they herald an interest in exploring the politics of style and technique that is easily as complex as his exploration of the politics of content. Not that content is missing. The "Men at Work" paintings--again, appropriations of obscure, uniquely stale, documentary photography--aggressively return to the pin-up. They draw sly comparisons between serious study and casual voyeurism, suggesting that either one can be an excuse for the other. Adams has a keen appreciation of the wide-ranging cultural roots of the vulgar pin-up as well as an honest admiration for pin-ups as engrossing images in their own right.

Clearly, the paradox still holds. What these paintings show is that Adams the painter is developing an ever more powerful visual shorthand to express the eloquent narratives of Adams the cultural skeptic.

Forum Gallery, Jamestown, 1996